Alexander Michael Kent

Student Number: 200046947

197L Society, Space and Place MA

Department of Geography and Earth Sciences

01/09/2024

PDF Featured at bottom

DECLARATION

This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being

concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree.

Signed: Alex Kent (candidate)

Date 01/09/2024

STATEMENT 1

This work is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where

*correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly

marked in a footnote(s).

Other sources are acknowledged (e.g. by footnotes giving explicit references).

A bibliography is appended.

Signed: Alex Kent (candidate)

Date 01/09/2024

STATEMENT 2

I hereby give consent for my work, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for

inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside

organisations.

Signed: Alex Kent (candidate)

Date 01/09/2024

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the support of my supervisor Dr Mark Whitehead for guiding me consistently throughout this process, I would also like to acknowledge my mother and Chloe Griffiths for their support.

Abstract

This research project focuses on behavioural changes and awareness of artificial intelligence and algorithms within social platforms online. The methods used for this analysis were an electronic survey that received 112 respondents and an in-depth interview that lasted just over half an hour. The pivotal conclusions of this research found that people claim they are aware of artificial intelligence even before completing the survey, that included a concept that was unknown to most (the filter bubble). When discussing how they are aware and their further concerns, many noticed the personalised nature of social media algorithms, using terms such as ‘information cocoon’ and ‘echo chamber’, there was also an acknowledgement of the growing presence of bots online. The will to change seemed to favour a positive correlation, but not by as much as expected with over 40% preferring no behavioural changes. Additionally, there were mentions of theories such as ‘The Dead Internet Theory’ which could link in with a state of hyper-awareness, where people begin to potentially suspect and analyse actions that are not happening. The acknowledgement of a flawed AI that still shows its inability to become indistinguishable from human action or creation was further discussed in the interview. There was also a strong consensus on the concept of a filter bubble being a bad thing, and something that could skew information, reinforce bias beliefs or push misinformation to further polarize.

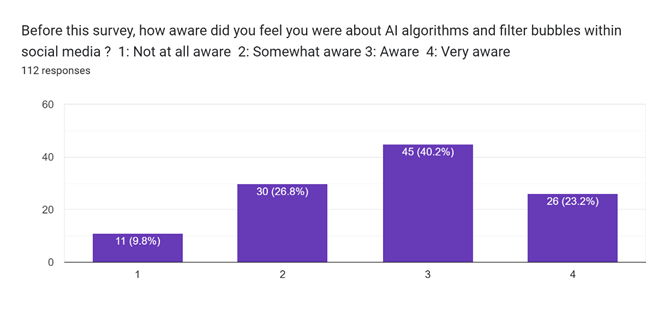

1: Introduction To the Research Project

This research project looks at two primary questions, the first, to what extent are users aware of the operations of AI on social media platforms? The second, how effective are algorithmic filter bubbles when the user is aware of them? The methods used to answer these two questions were qualitative in nature, consisting of an online survey which garnered 112 responses, and an in-depth interview. The term ‘Filter Bubble’ is somewhat criticized for being vague or its definition not solidified. Due to this, the question within the survey defined the filter bubble to which the research pertained, so that there was no ambiguity around the meaning. It is further important to note that the focus of online behaviour was solely on social media platforms, and awareness around the personalising algorithms along with its potential to change users’ behaviour. When discussing AI, as is elaborated in the literature review along with the discussion aspects of the data, the focus here is on personalised content ecosystems. Whilst things such as misinformation, political polarization, data harvesting techniques and image generation are a part of AI, they are only mentioned when relevant as the focus is more on the human’s perception of AI than what AI can do within a filter bubble. The relevancy of this research lies within a niche subject area of social science and artificial intelligence, as much of the focus is on AI’s capabilities and not the level of awareness the average person has. This, in fact, identified multiple areas that require further research, such as a hyper-awareness of AI and how aware are people on the methods AI uses to harvest their data such as audio and voice data. This research could also be useful to literature around concepts such as social architecture (Mills & Skaug Sætra, 2024) nudging and hyper-nudging (Morozovaite, 2023; Whitehead, 2019; Wagner, 2021) and information cocoons (Sunstein, 2006). The survey allowed a percentile measurement of awareness surrounding AI algorithms, finding that 90.2% of the 112 respondents had a positive awareness level of AI before filling out the survey questions. The structure of this research will follow a review of relevant literature surrounding the areas that this research is associated with and could be useful to. Then, the methodology of how the data was garnered, along with the ethical practice and limitations of such methods including further lamentations on how to improve these areas. Finally, a discussion on the data found including direct quotations and percentages, along with illustrations from the survey data and other relevant data before a conclusion is met and analysed.

2: Literature Review: Filter Bubbles, Social Architecture and Subliminal Nudging

2:1 Introduction

The aim of this literature review is to analyse the relevant studies and research surrounding the pivotal content of the research question of this study ‘What is The Effect of Artificial Intelligence Awareness When using Social Media?’. The literature review focuses on the evolution of algorithms that personalise the content that we consume, whilst discussing Eli Pariser and the creation of filter bubbles, a concept derived from the book ‘The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding from You’ (Pariser, 2012). The review ends with a look into nudge theory and social choice architecture, and how this subtly influences the decisions that are made online for an ulterior agender. Nudge theory was originally created by Thaler and Sunstein and focused more so on health and income, with real life examples of nudge theory being the prime examples used (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). The literature looked at in this review, however, is of nudge theory in the context of artificial intelligence, algorithms and online behavioural changes that are caused by this.

2:2 History of algorithms

Before the advent of AI assisted algorithms and personalised online experiences, posts and content were shown chronologically. It was quickly seen as something undesirable to social media companies and users alike, as it often ended up removing relevancy of posts and becoming more disorganised and spam-like (Santilli, 2024). Algorithms, whilst now heavily associated with AI and online spaces, is essentially a symbolic word for a set of processes that leads to a solution of a problem. With this definition, algorithms can be traced back to the earliest Babylonian mathematics. When tracing it back to its more modernised origin, it can be sourced from renown early computer scientists and mathematicians such as Ada Lovelace. With the use of the analytical engine, Lovelace programmed an algorithm called ‘Note G’, that calculated sequences of bernoulli numbers (fractions that appear in analysis calculations), this later became the first computer programme (Abitebou & Dowek, 2020). It is worth nothing that whilst artificial intelligence is seeing a meteoric rise in usage, it is by no means as new as many would thing. AI has seen itself rising and falling for over 70 years in terms of usage and efficiency, these falls where AI has lost favour with stakeholders has been termed as ‘artificial intelligence winters’ (Muthukrishnan, et al., 2020). There have been two major ones, with the first arriving in the mid 70’s and ending in 1980. The most notable being that of the IBM and the end of Japan’s supercomputer known as the ‘fifth generation project’ during the 90’s (Muthukrishnan, et al., 2020). Some researchers believe that the current boom in AI will see a third winter, due to companies’ overconfidence in AI when it still lacks fundamental human traits such as common sense. Whilst others point to the subjectivity of these kinds of terms, research in this area has shown that when people believe they are speaking to another human and not AI, they attribute the human traits that AI supposedly lacks. (Mitchell, 2021; Ashktorab, et al., 2020). As Sherry Turkle argues, AI in social media is not just doing things for people, but doing things to them that they are not aware of. We tailor our lives around our online life, so humanising AI is inevitable as AI is built from humans (Turkle, 2011).

The first algorithm that saw utilisation in mainstream content organisation was known as ‘The Edgerank’ algorithm, used in Myspace and Facebook to recommend friends and organise content on the newsfeed in terms of relevancy for each user. Early criticisms of Edgerank argued that because of its ranking operation, it could potentially create an echo chamber of content for users and shield them from seeing wider contexts and conflicting information (Andreas & Carlsen, 2016). When looking at research from the time that this algorithm was relatively new, there are concerns about its potential that have become accurate. This can especially be seen around surveillance and the lack of privacy that AI could potentially produce. With a Foucauldian approach, it is argued that the user becomes the mere sum of their parts, no longer seen as a human and instead a data point to be used. Algorithms and their ability to influence decisions also highlights a relevant risk, the governance by data and the commodification of the individual. Additionally, concerns over algorithms and their inner workings, and how much of this is kept secret or ambiguous so that competitors on other sites are not able to harness any information for their own algorithms is still a present problem. Continuing along the Foucauldian line of reasoning, it is argued that instead of the subject becoming the centre of all surveillance, instead they are reduce to mere data, and become invisible and nullified (Bucher, 2012; de Laat, 2019).

Eli Pariser in a book titled ‘The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding from You’ (Pariser, 2012) first coined the term ‘filter bubble’ as a concept of what algorithms are capable of. Pariser posited that AI was defining you not by the content of your identity but by demographic means such as income, location, age and sex. Essentially, those who use the internet become a consumer and the one consumed, we no longer have individual autonomy over our choices. Instead, our choices are made for us designed on what the AI thinks is best for us. We are presented a stream of seemingly endless content online, yet our knowledge of how this stream is created is abstract and unknown to us (Pariser, 2012). Whilst at face value a lack of open barriers within content influxes seems reasonable and even preferable for many users, there are concerns. The main concern scholars, policy makers and researchers have alike is that only being exposed to one type of content and information can lead to extremism. Echo chambers are unproductive for understanding the nuances of an event or view; therefore, a polarisation of beliefs can occur on a much larger scale and sharper dynamic. False information or distorted information can cause mass hysteria, extremism, and a further widening of gaps in homogeneity within society. Views are bolstered ten-fold by likeminded individuals in a plurality, thus giving it the illusion of more evidence and legitimacy (Daus, 2024). Radicalisation and filter bubbles have seen evidence emerging from social media mainly, with machine learning algorithms creating isolated anomic users because these kinds of users are more likely to produce content and consume it. The issue with AI, something that has been seen before when discussing AI’s ability to rise and fall, is that it moves rapidly through technology and its advancements. Due to this, researchers are unable to acquire appropriate tools to track and bookmark its pivotal moments, and in a turn of phrase, left in the dust. Consistently having our desires for content and items that meet our subconscious specifications creates a strong bond and addiction to the fruits of machine learning algorithms labour, unfortunately user awareness of this manipulation is not entirely enlightened (Rodilosso, 2024).

With the number of social media users nearing 5 billion, the content that we interact with is undeniably of high importance both in terms of information and consideration. The standard algorithmic behaviour within social media is to show the user content that both meets their expectations and keeps them engaged with the site. Through doing this, however, a filter bubble is created, a tailor-made world of content that fits your preferences, opinions, likes and engagement (Rodilosso, 2024). A study in South Korea found that users accept affirming personalised algorithms controlled by AI at a higher rate over diversity algorithms, in-fact, personalised algorithms are often a better measure of the AI’s usefulness because of this (Cho, et al., 2023). However, filter bubbles are not simply keeping every user in their own separate world in terms of every form of content. In news, a study showed that the top five publishers reached over 99% of users on social media regardless of their political stance. In fact, much of the news related content is dominated by the top five news related media outlets, and as such a filter bubble in this regard is not exactly achieved in the way it is thought of (Nechushtai & Lewis, 2019). Others argue that the potential endless reinforcement of views through filter bubbles can lead to extremism or indoctrination, along with a stream of potential endless misinformation (Rodilosso, 2024; Areeb, et al., 2023). A large part of the problem lies within the definition of a filter bubble, many tools that address the issue even lack a definition of what it is that they are fighting against. Moreover, many of these tools and the perceptions around filter bubbles are almost exclusively based in the US or US politics (Bozdag & Van Den Hoven, 2015). Research into echo chambers has further called for emotions and its role on behavioural change to be taken into consideration more. Studies have shown that anger in online behaviour translates to more trigger responses to opposing opinions and a further theoretical hibernation into a personal echo chamber to subdue the emotion (Wollebæk, et al., 2019).

2:3 Demographics and Personalisation

Social media algorithm creators say that the use of filtered out content is a direct AI act to stop an overflow of information on users. However, it is acknowledged that this can and will most likely cause of filter bubble of personalised content. In a study focusing on 140 participants and Facebook specifically, many requested a specialised tool that would allow them to escape this filter bubble and experience things out of their designated content (Plettenberg, et al., 2020). This was presented during a conference in Denmark, and Facebook replied that the user can in-fact escape their filter bubble by going through the settings and categorically deleting all cookies that may be personalising their content. Moreover, in Denmark, the youth typically claim to have a high level of awareness of their own filter bubbles on social media, including the news media that they consume. However, when their internet behaviour has been analysed, it has shown the opposite, meaning that even an awareness of a filter bubble does not mean that the user is invulnerable to its echo chamber effects (Lensink, 2020). Further research into demographic information and filter bubbles has discovered that age correlates with an increased time online and desire to see the news as it develops via social media news feeds. Additionally, females consumed less online news media than males, but both demographic points had a significant but not large effect size on falling into filter bubbles (Sindermann, et al., 2020).

2:4 Critical Literature on Filter Bubbles

Literature regarding filter bubbles is not always so sold on its existence, as it is argued that the term is vague and rarely concretely defined. It is also interchangeable with the idea of an ‘echo chamber’, with it at times being used as a one lump term. Google, regardless of personal data it must tailor experience, will often give the same search results to individuals. With it being argued that google news is not diverse enough, rather than creating a personalised universe for the user (Pérez-Escolar & Noguera-Vivo, 2020). Additionally, a survey consisting of 271 Facebook users found that many individuals report seeing content outside of their filter bubble, that when pinpointed down stems from acquaintances or non-close friends they have on the site (Min & Yvette Wohn, 2020). Other researchers claim that the filter bubble is a convenient technological-based moral panic to distract from the ever increasing political and social divides going on within society. The argument made here is that humans have become less open to contesting opinions and arguments that may undermine or disprove their personal narrative due to societal polarisation rather than evolving segregating homogeneity bubbles designed to elicit an endless self-perpetuating feedback loop (Bruns, 2019). However, the most common argument is both the lack of definitions around filter bubbles and the lacking empirical evidence around their operation with users online. This calls into the question of one, how effective filter bubbles are and two, if they are truly separating us into our own personalised worlds of online content (Michiels, et al., 2022). A further literature review that looked over 55 studies revolving around echo chambers more specifically concluded that much of the research conducted is sullied due to its mixed method approach and biases. The review posited that self-reported data and digital trace data are conflicting, therefore they are more prone to skewering results and bias. It is further worth mentioning that this literature review focused on social media site related research as its foundations (Terren & Borge-Bravo, 2021). Additionally, there is a disparity between empirical data and theoretical data, as the subject of AI is still in its early stages much of its impact is through hypothesis and theoretical outcomes. Studies have tried to create a quantitative metric to measure filter bubbles and echo chambers, to pinpoint their inception and define them cohesively (Mahmoudi, et al., 2024).

One study utilised a unique methodology of ascertaining the creation of filter bubbles and its spread of misinformation. This was performed by creating sock puppet proxy accounts on YouTube that were essentially blank slates. The accounts would then dive into rabbit holes to see the levels of misinformation the filter bubble would create through algorithms. The study found over 17,000 videos recommended to the accounts, with 2914 being identified as misinformation manually by the researchers themselves. The data was then used in a machine learning algorithm of its own to help create systems that are better at identifying misleading, misinformation filter bubbles (Srba, et al., 2023). Others claim that the answer to combating the existence of filter bubbles is to diversify the very algorithms that are creating them, rather than the production of anti-filter-bubble AI (Spina, et al., 2023).

Filter bubbles and their existence, despite the scepticism, have been shown through many studies. One of which saw two individuals google Egypt, with radically different results being displayed. One result had shown the protests and political unrest in Egypt, whilst the other had not. Filter bubbles, some may argue, are inherit in human behaviour without the need of technology, and AI is only reaffirming natural human patterns (Beinsteiner, 2012). Humans are inherently biased to some degree, and this will always be present in sort out information and interests regardless of personalised ecosystems created by algorithms. The problem is that these ecosystems are reinforcing biases rather than widening the view of information that we consume (Saxena, 2019). Social media sites and their business models often rely on these artificially created ecosystems, as sites like Instagram and Facebook offer advertising and viewership boosts to the users and their own businesses. The content these creators boost will then be shared to further users with similar interests and who encompass the same ecosystem, creating and reinforcing a feedback loop of content creation and consumption. Each stage of the boosted post is categorized by the algorithm using relevant hashtags, and by analysing the filter bubbles of the followers and recommending the post to the majority categorisation. Each data mutation further embeds the ecosystem into the users experience and teaches the algorithm how to more effectively content farm. Sites like Instagram or TripAdvisor offer additional support users as this process undergoes its stages (Alaimo, et al., 2020).

2:5 Nudge Theory and Choice Architecture

For algorithms to understand human behaviour, they must constantly collect and present data to us in the everyday, to understand our routines and patterns and then compartmentalize these astronomical quantities of data. Decisions that we make online have been argued to have the illusion of free-will choices but are guided by algorithmic nudges. This is referred to as ‘choice architecture’ within algorithms (Beer, 2019). These nudges are presented in hints, warnings, reminders and recommendations. Policymakers have been utilising and showing interest in machine learning algorithms that are able to shape populational consensuses or habits through these choice nudges. An example of this is recommended sites or searches on health conditions as diabetes is on the rise. It has been concluded within this research that choice architecture is not that useful on an individual level, but when blanketing sub-populations, it can have a large effect (Hrnjic & Tomczak, 2019). Much of this research stems from what is known as ‘Nudge Theory’ (the theory of subtle subliminal alerts altering our behaviour online to a more desirable usership for policymakers or big companies). The theory posits that people are more likely to stick with a default rather than tailor their own experience. The evidence for this can be seen in the changing of people to organ donors as a default rather than the opposite, and how as high as 98% of people are organ donors. Intelligence for AI is defined as selecting actions that are likely to achieve the desired outcomes, this negates much of the stereotypes around AI and sentience in favour of a more realistic manipulation of human behaviour through pattern recognition (Mills & Skaug Sætra, 2024).

Nudge theory is not all data manipulation and subliminal control, as there are also websites such as ‘X’ and additional literature that investigates the control of misinformation through these nudges. This is usually achieved by notifications or flagged icons that shed light on the wider context of truth of the post so that misinformation spread is avoided. When an event or information is becoming released into the public, people often use social media as the source of information about the situation as it can often be much quicker in releasing all the data. The problem lies within resharing information that is not accurate, and therefore spreading false data that have real world consequences, with fact check nudges this spread can be minimalised for the greater good (Pennycook & Rand, 2022). Moreover, nudges have been used to help combat social media addiction and passive usage that can extend into large consumptions of time. This is done by nudges that remind you that you have been on a single app for a certain amount of time, forcing your usage to become something conscious rather than passive subconscious scrolling. Much like the research discussed in this dissertation, this focuses on awareness and how this changes the behaviour of our interaction with the online world (Monge Roffarello & De Russis, 2023). It has been shown that people under the age of 35 use social media as their preferred method of staying informed with the current updates and news. However, as passive scrolling and social media addiction become more of an issue, it has also been recorded that attentions spans are dropping. Therefore, nudges that lead to clickbait, easily consumable and incomplete/ not well-informed articles are becoming not only more prominent but also the preferred source of information over what is traditionally considered as ‘hard news’. Facebook, despite having an older user base, is notorious for using and favouring these kind of clickbait, punchy articles over in-depth traditional pieces (Jung, et al., 2022). There is a further iteration of this created by Karen Yeung that is known as ‘Hyper-nudge’, this combines the subtle course altering effect of a nudge into a group, along with its adaptability to the user’s behaviour. This adaptability and dynamic behaviour are where it separates itself from regular nudge theory, as it is all about steering people into the right content bubbles. This concept is relatively new, however, there is a growing concern over how hyper-nudges could create collective harms and polarise homogenous values within society (Morozovaite, 2023; Mills, 2022).

2:6 Conclusion

The reviewed literature shows that with concepts like nudge theory and filter bubbles people are more likely to let the algorithms dictate what is shown to them rather than going out of their way to personalise their own content or disrupt the creation of a filter bubble. Additionally, there is a lack of clear definition around the term ‘filter bubble’, something that when referred to in the research methods of this dissertation, a strong definition was provided. Academics debate the relevancy of filter bubbles, with some claiming that it spreads misinformation and polarisation, and others criticising its very existence with examples of the same top news outlets being the source of everyone’s information despite personalised content. Youth claim to have a higher awareness level of what and how AI is manipulating their behaviour online and their data, whilst females tend to consume more news in real life mediums rather than purely online. Despite academic criticisms on the definitions of filter bubbles and if they are possible to measure or truly exist, artificial intelligence algorithms and their subsequent success are measured on their ability to content farm by creating online ecosystems and echo chambers. With 5 billion users on social media alone, AI and its ability to flourish must be kept track of, as another ai winter event looks unlikely and over 62% of the world’s population is subject to the evolution of AI driven algorithms.

3: Methodologies and Ethics

The key methodology of this research was conducted via an electronic survey, the questions within the survey included many open answers so that longer and more in-depth answers could be given for choices made on previous questions. The aim of this survey was to measure awareness and its potential on behavioural change online. This is something that has been touched upon in other studies across academic fields and which often used the Likert scale as a key form of measurement (Sutton, 2016; Falk & Anderson, 2012; Rew, et al., 2003; Wang, et al., 2023). The use of the Likert scale within this study varied from a 4-point to a 6-point scale when appropriate. The advantageous thing about the survey is that it allows the participants to self-guide themselves and analyse their own perceptions of their awareness through scale answers. This is then followed by an open answer box asking for the participants to explain why they had measured themselves the way that they had. The survey not only sought to measure the participants awareness of AI algorithms but also filter bubbles, with a question informing the participants on what exactly is meant by a filter bubble and a pre and post assessment on their awareness of this concept since completing the survey. General demographic information was also collected as early questions within the survey, this information is useful in sorting out potential correlations within certain groups and their overall awareness of AI, e.g. age and awareness.

One of the benefits of using an online survey was its ability to recruit mass responses in a quicker succession of time. Its delivery system was propagated via a simple link that would take participants directly to the survey, cutting out any ambiguity to its location. The reason an online survey was an attractive form of qualitative research is that it allowed participants to save their progress and return to it later, removing the rushed manner an in-person survey may create (Braun, et al., 2021). The average response rate to online surveys is around 44%, and studies on this have shown that when circulating surveys through the internet it is better to carefully curate the audience that it is sent to rather than taking a less careful and more blanket approach. This is something that the author felt highly necessary when sending the survey used in this research, as both the response rate and the responses were taken into high consideration (Wu, et al., 2022). Online data collection is known for its speed in data gathering, however, as previously mentioned, this is not aways ideal. One of the reasons for why the author and other researchers in this method avoid mass spread is because responses online can be inauthentic, answered instead by bots. This is not an issue that physical surveys encounter, however, it is something that can happen easier than imagined for online data collection methods. In-fact, the scientific communities within academia have had an issue over the last few years with bots taking their surveys and producing false and low-quality data, this has become an issue enough that papers on how to prevent this have begun to be published in journals. The main strategies highlighted for this prevention were heavy consideration on research pooling samples and if bots are still suspected, captcha protocols can be implemented (Storozuk, et al., 2020).

A disadvantage that was considered as it could change the nature of the research methodology was that surveys are not scheduled or within a time restraint for participants. This meant that there was a chance that not enough ample data and responses would be collected before personal deadlines for the analysis and the discussion of the research objectives had to be completed (Nayak & Narayan, 2021) . Thankfully, in the case of this study, the online survey performed better than expected totalling 112 respondents when the initial aim was 50-75. Additionally, there are multiple proven ways in improving response rates for surveys, some of which were utilised for this study. The methods to improve response rates are reminders on distribution pools so that anyone that has missed or forgotten to complete the survey have a second chance. Designing the survey in a way that encourages the participant to complete it, for this survey that involved a limit of 11 questions with 5 being open dialogue boxes so participants could control the length of their answer. This use of open text was also used to encourage a less controlled and rigid dialogue. The use of the university weekly bulletin was also advantageous, as it supplied access to specific potential respondents who are more likely to be aware of AI as it is potentially a part of their studies (Shiyab, et al., 2023).

Additionally, within the survey the goal of data collection was not just awareness, although it was the priority. The further goal was to see if people who knew of personalised content and what levels their personal content was being personalised for them were considering changing their use and behaviour online. There were two recommendations given after these questions so that the participants did not feel the question was ambiguous, that of exploring content outside of their filter bubble and avoiding personalised content such as adverts. The in-depth survey was then distributed to university students of Aberystwyth through the weekly bulletin board, a personal post on Facebook and a further sharing by the supervisor of this study to potentially interested participants. The purpose of this study was to see if there was a correlation between AI awareness and how this effected an individual’s behaviour online. Definitions for filter bubbles along with specific examples were provided within the survey so that the participants felt that they were guided by the questions but not restricted, and that nothing was ambiguous. Within the synopsis and disclaimer that read before the survey began it was highlighted that the focus here was on social media, and that data was both anonymous and that participants had no obligation and could opt out at any time.

Within the opening dialogue box of the survey was an address to the authors email and an expressed desire for interviews with any participants that were interested. Despite this, none of the participants or observers of the survey did contact the other, so the only interview was conducted via an already pre-agreed arrangement. The interview was in-depth and in-person, it was flexible in questioning focusing more on the flow of rapport than specifically highlighting a rigid structure line of motion. The interview was conducted in the library of Aberystwyth University in a private room, the audio was recorded and transcribed for the purpose of dissecting and analysing for the use of this dissertation. The questions, whilst relaxed and improvisational depending on the flow of discussion, still followed the theme of awareness of artificial intelligence and how that can lead to a change or non-change in behaviour online. The questions delved into definitions of AI more broadly, something that the survey did not, and additionally explored the potential risks. The objective of this interview was to hear an informed opinion from someone who had experience with AI being used in their research field and the potentialities of this usage. The interviewee was a friend who the author had previously attended an AI symposium with where they had a segment discussing AI in their field of work. The semi-structured interview lasted half an hour, after which the discussion reached a conclusion from the participant that did not feel laboured or repeated. Additionally, the participant is a student and has studied AI as part of the course that they are currently on.

The idea of following threads that allow for fruitful digression on potentially untouched areas of awareness and behaviours surrounding the presence of AI was the reason that a semi-structured interview was desirable overall. Whilst there was a structure to the questions that followed the theme of awareness and filter bubbles, the discovery aspect of free-flowing conversation proved to be advantageous (Magaldi & Berler, 2020). Additionally, semi-structured interviews have proved to be useful when exploring the potentials of AI and what it means to everyone (Wasil, et al., 2024). In further research that explored the role of what artificial intelligence means to teachers of varying degrees of awareness, the semi-structured interview was found to be the best way of collecting data on how they defined it. Whilst the study of this paper focused on awareness, a solid interview that discussed definitions around AI and its capabilities was useful to the overall data and gave a more in-depth analysis into the foundations of perceptions on AI (Lindner & Berges, 2020). The issue and ethical consideration with the qualitative interview were that it is more prone to subconscious research bias, as it is in the format of a conversation where input and facial expressions, tones of voice could potentially affect the answers being given by the participant. This issue has been touched upon by a paper that also used qualitative interviews as a form of research int the acceptance of AI, with it being decided that the potential for bias was acknowledged but the exploration of potential hidden aspects of the subject matter was essentially worth the risk (Hasija & Esper, 2022).

The flexible nature of the interview also allowed for adaption, something that propagated richer data that could be use in correlation with the open text box survey results to gain a fuller picture of the way in which people are aware of artificial intelligence and its potentials for behavioural change. As discussed in a paper on the advantages of interviews in developing detail within qualitative research, the interview plays the role of both mining for the data wanted and travelling with the participant on a pathway to novel data potentials (Ruslin, et al., 2022). Moreover, the interview can connect the reader to a greater understanding of the direction that the research was implemented and the themes that are explored. When coupled with surveys, interviews are great at dissecting the usefulness of certain quantitative data such as demographic information provided by surveys. The idea behind mixed methodology is that it creates a breadth and depth for analysis, covering all bases. The phenomenology behind the behaviour change is vital in understanding the data, and this is achieved most fruitfully through qualitative means such as an interview on experience and awareness (Knott, et al., 2022). However, as previously touched upon, biases and ethical concerns can be more prevalent within interviews as the anonymity to the researcher is no longer there. On a similar vein, there is a stronger sense of curtailing the data for interviews as they can potentially be more revealing, and it is an ethical duty of the researcher to keep all participants anonymous. This is for the personal protection of them as an individual and the data they have given for the research question. The participant must make sure to meet the criteria of the ethics forms filled out, including that they are not a part of a vulnerable group that has not been accounted for. Additionally, the impact that the interview and impromptu questions could have on the mental wellbeing of the participant must be taken into deep consideration, so that the interview is conducted fairly and safely for all involved (Husband, 2020).

The interview provided rich data that complimented the 112 responses that the survey had garnered, no more interviews were conducted as the survey had performed better than anticipated and the author felt it important not to have too much data spread too thinly over the course of this dissertation. The interview was kept because it gave a personal insight into the use of AI in everyday life and its ability to alter behaviour from another perspective that could flow in real time. The reason for the importance of keeping this aspect of the data is that although the survey provided multiple text boxes for further explanations, a typed response will always differ to a live discussion in-person. Having both allows the author to compare/contrast revised or edited text responses vs responses that are less tailored yet more engaging. It is further worth mentioning regarding the survey that the spread and availability was somewhat contained to other students/academics and personal online communities known to the author to prevent potential null/antagonising responses that could harm the validity of the study.

3:1 Limitations of the Surveys

Before ending this section, it is worth noting that there were a few limitations with the survey. As just mentioned, due to an overdue diligence on garnering non-AI responses, the survey was only circulated in certain communities. Many of the people in these communities worked or were academics, due to this, the overall awareness of AI and its effects may have been higher than a more randomised and diverse sample. Additionally, this survey received criticism from one of the participants regarding its structure, specifically how it handled age demographics. The participant said that 31-50 is too broad an option, and this could be seen as potentially ageist from the researcher. This is a criticism that has some merit, and in the future more attention to categories within the demographic options will be noted (such as including location also).

3:2 Limitations of The Interview

Whilst there were no real limitations regarding the interview itself, if the project was larger more interviews would have been conducted. With knowledge also now of lacking subject areas within the field of AI in social science, those questions would have been asked. Additionally, the interview was conducted before the results of the survey, so much of it treaded similar ground due to the unknown success of the surveys circulation. Perhaps, in the future, surveys would be allowed to circulate first before any interviews were conducted.

4: Findings and Analysis Discussion: Surveys and The Interview

4:1 Demographic Data

The surveys garnered 112 responses by the end of the deadline, which, as previously stated was more than anticipated and meant that only one interview was needed to accompany the mixed methodology. In terms of demographics, the bulk of the respondents (45.5%, or just under half) were in the 21-31 age group, with 27.7% of the respondents being in the 31-50 age category. Only 7.1% of the respondents fell in the 18-21 age ranges despite it being shared out to all students on the weekly bulletin, with over double the respondents of that (19.6%) being 50 and over. In terms of gender identity, the split was in favour of female, as out of 102 responses, 53 identified as female and 44 identified as male, there was a further 1 non-binary respondent (demigirl and xenogender) and 4 responses that were void (white, prefer not to say, La bar and a link back to the survey). With the survey data showing a higher response rate from females compared to males, it is worth highlighting the rise of offensive and discriminatory AI recommended content on social media that many women have flagged up as an issue. It has been suggested that as sexism, discrimination and misogyny are prevalent in real-life to a concerning degree still, with the ability of anonymity online this has become prevalent even more so on online spaces. The concern is that AI algorithms do not necessarily recognise some forms of offensive material, or the algorithm itself is more concerned in generating an endless stream of content to keep users engaged. This can lead to an influx of content that is deemed sexist or discriminatory being recommended to certain demographics (Shimi, et al., 2024). Judging by the answers to this research in correlation with age brackets, it shows that people of all ages are using social platforms be it passively or more in-depth. Whilst many of the respondents fell into stereotypical age ranges for social media use 21-31, the second highest number of respondents were 50 and over. When looking at later data within the survey pertaining to personalised content in social media specifically, the highest responses indicated positively to this. Interestingly, 18–24-year-olds are most likely to use Instagram or TikTok as their social platforms of choice at over 75%, whilst 50 and over groups tend to use Facebook and YouTube at around 50% (Auxier & Anderson, 2021). Despite the differences in platforms, both Instagram and Facebook are both owned by Meta and function in similar ways.

4:2 Likert Scales Discussion

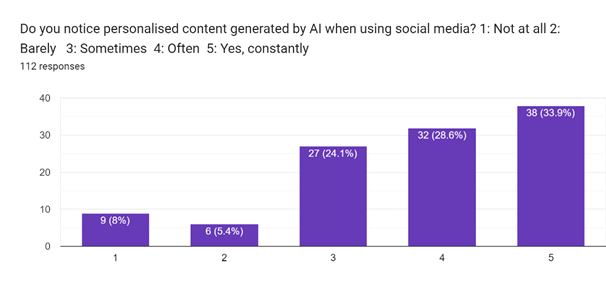

The first of the Likert style questions was question 3 ‘Do you notice personalised content generated by AI when using social media?’, the answers available to this question 1-5, with 1 being ‘Not at all’ and 5 being ‘Yes, constantly’. Not surprisingly, the two highest responses were 5 ‘Yes, constantly, at 33.9% and 4 ‘Often’ at 28.6% of responses. The lowest was answer 2 ‘Barely’ which received 5.4% of responses followed by answer 1 ‘Not at all’ which received a slightly higher 8% even. Answer 3 ‘Sometimes’ being the more moderate of the answer options available on the scale received 24.1% of responses. All respondents answered this question as it was marked mandatory for the completion of the survey by an asterisk (See Appendix A).

The two-fold purpose of social media is to keep the user interested in the content being generated and avoid cognitive overload. The way in that this is usually done by algorithms is by feeding the individual data that falls in line with their pre-existing opinions and beliefs, strengthening the user’s self-validation (Pasca, 2023) The ‘fast greedy’ algorithm, a computer science algorithm that detects communities in echo chambers or filter bubbles has been hypothesized as a potential key to finding and measuring filter bubbles within groups. Use of algorithms to detect online ecosystems has been criticised, however, for its potential ethical implications in singling out certain groups or beliefs. The counter argument to this is that it is unethical to feed users potentially false information for the sake of keeping them invested in using the social media of their choice (Alatawi, et al., 2021).

As the data from question 3’s research shows, 62.5% of people chose the two highest options available on the Likert scale, and if combining the moderate option ‘sometimes’, that is 86.6% of respondents noticing some form of personalised content within their online experience. As previously discussed in the literature review chapter, algorithms not only use pattern recognition algorithms to detect user preferences, but this data is also used to nudge the users into decisions that may be advantageous for the app that they are using. To take this further, hyper-nudging has been hypothesized to act in a similar way, guiding the subconscious decision making of people, but on a macro scale. The everyday for individuals is no longer a personal phenomenology that’s secrets lie behind duality themes of consciousness, but instead it is an ocean of knowledge production, consumption and evolution for AI (Whitehead, 2019). According to the DATAREPORTAL, the average person online spends just under 2.5 hours or 143 minutes on social media a day with over 94% of internet users having a social media account. To put the potential manipulatory effects social media can have in perspective, the world spends on average 720 billion minutes on social media a day, with a staggering 500 million years of combined human social media consumption a year (Kemp, 2024). When coupling this with recent data on the effects of time spent on social media, it has been found that more usage causes greater risks of depression, especially in adolescents (Liu, et al., 2022).

However, it is worth noting that an 8-year longitudinal study that looked at 500 participants aged 13-20 found no link between detrimental mental health effects and screen time, including time spent on social media (Coyne, et al., 2020). In the recent research in this issue, it is posited that the way the data is split and interpreted is what leads to the conflicting results on screen time and its potentially negative mental health implications. In summary, the vast amount of time spent on social media on a global scale is not necessarily a problem, with only small positive effects that are short lived tracked when quitting social platforms (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, 2024). Taking it back to the results of this question, a high majority of people are noticing personalised content, coupling this with a potentially significant amount of daily exposure to this content. However, the data on if this is negative to the users is ambiguous, but it does lead to an interesting thought on the high amount of overall time spent on social media globally. With so much time spent on social platforms and so many individuals noticing personalised content in their experience, it is clear the seemingly endless amount of data AI algorithms must dissect is a major factor in its rapid evolution. The next Likert scale question looks at the concerns people may have over this rapid evolution and the overall integration of AI into daily life.

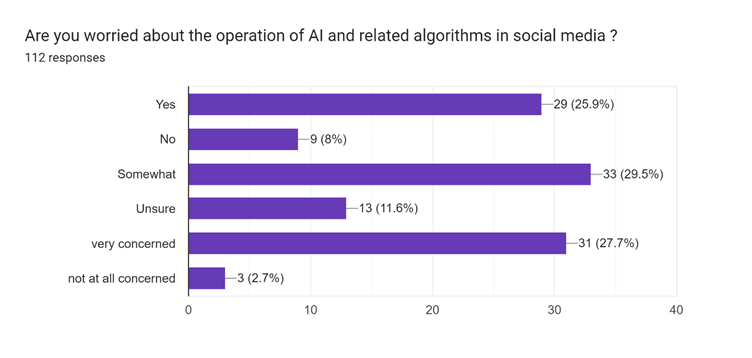

Question 4 ‘Are you worried about the operation of AI and related algorithms in social media?’ was another Likert scale question, this one being a 6-point scale. The spectrum of the six answers are as follows, 1 equalling ‘Yes’, and 6 equalling ‘Not at all concerned’, again this was a mandatory question for the completion of the survey and was marked by an asterisk (See Appendix B).

Interestingly the middle ground was the highest response rate here, with 3 being ‘Somewhat’ and receiving 29.5% of the responses. This was closely followed by answer 5 ‘Very concerned’ which received 27.7% of the responses. The third highest response was again on the side of concern, with the flat ‘Yes’ as answer 1 receiving 25.9% of the votes. The findings here strongly suggest that there is a concern with the involvement of AI in social media, even if it is on the more subdued side currently for most respondents. Answer 2, which was a flat ‘No’ only received 8% of the responses, with answer 6 ‘Not at all concerned’ receiving the lowest percentage of all responses at 2.7%. This moderate concern could be down to the obvious nature of algorithmic behaviour in generating content, as previously established, most respondents have noticed their content being personalised for them. When looking at research conducted on Reddit that delved into content analysis of both tech related subreddits and non-tech related subreddits. The concerns for tech-centric forums focused on technological capabilities of software, whilst non-tech-centric subreddits instead shifted its focus towards the potential social impacts of AI (Qi, et al., 2024). The following section, which was an open text box asking respondents to explain their answer, showed a high level of concern over the social implications of AI.

One respondent wrote.

“On the one hand, algorithms may lead to the formation of information cocoons. Social media recommends personalized content for users through algorithms, which may enable users to directly achieve information similar to their own views and interests and exacerbate social differentiation and confrontation by limiting the expansion of vision and thinking. On the other hand, algorithms can also be used to spread false information and undesirable content. These bad actors may take advantage of the loopholes in the algorithms to spread misleading or harmful information on a large scale, which has a negative impact on public opinion and public safety.”

This answer touches upon subjects surrounding the potential for misinformation to create wide gaps of social and political polarisation, something that, as discussed previously in the literature review, can lead to extremism (Rodilosso, 2024). The other interesting part of this answer is the mention of ‘bad actors’, this can be groups or individuals that exploit technology to push malicious or wrongful content/information. One of the largest threats that is now being discovered in terms of bad actors is that they are often not human at all, but instead comprise of bots. Bots have seen a sharp increase in online spaces, for reasons of misinformation, rapid survey completion (something that was heavily considered when creating and circulating the survey for this research) and political or social polarisation. CAPTCHA is often used to prevent bots from creating fake accounts such as email addresses or social media profiles, however, as the landscape of the internet progresses technologically, so to have the way in which bots operate and exploit loopholes as mentioned above (Pozzar, et al., 2020). In fact, these bad actors being bots and not human at all was mentioned as concerns by several of the answers as shown below.

“I think that automatically generated content is “diluting” real content by real people, and it just creates an echo chamber of perpetuated ideas.”

“It’s scary when you see people sharing posts that are AI. Also, I’ve noticed so many comments on social media pushing agendas, and when you look at their profile it’s obviously an AI bot.”

“The internet becoming an echo-chamber for AI, literally AI bots just talking to each other.”

“Nowadays, AI and related algorithms are being used to manipulate social media. They create false prosperity by controlling robot accounts, making some people overnight internet celebrities with thousands of followers. These robot accounts like, comment, and repost every day, making these internet celebrities look very popular.”

One respondent referred to the ‘Dead Internet Theory’, writing.

“I am quite a big believer in the dead internet theory and now see a large portion of the internet as unnatural. Before, the internet was more wholesome and would be located in a singular place like a home computer/internet cafe, but now the internet is everywhere and therefore so is AI”

The dead internet theory posits that AI is far more ingratiated and ahead in our online environments than we realise, and that most of the internet does not consist of real people and instead, large swarms of bot’s content farming one another (Renzella & Rozova, 2024). The current updated Imperva bad bot report, a study that tracks the amount of bot traffic on the internet compared to human traffic, found that just under 50% of internet traffic is caused by bots (Imperva, 2024). Alex Hern of The Guardian writes that despite the evidence pointing to a large infestation of robot activity posing as humans, there are still social platforms with encryptions that can escape the bad actors. These social platforms consist of WhatsApp and Discord, where specific requirements are needed before conversations between individuals can begin (Hern, 2024). Whilst there is some evidence suggesting that parts of the dead internet theory are legitimate, as previous data surrounding social media shows, much of the internet is still heavily populated by real people. An interesting thought, however, is that if the internet consisting of 50% bots, with what it is estimated that around 5 billion people have accounts on some form of social platform. This suggests that we are living in a space where human and AI interaction is not always clear and much more prevalent than most are aware. Whilst many may dismiss the idea of a shared existence with incognito robots, from the data discussed along with the multiple answers from respondents, this is a reality and not a dystopian fiction. Moreover, the Turing test which was originally created to test the deceptive intelligence of a machine in its ability to convince the tester that it was human, is now seeing a reverse version. With anti-AI algorithms being integrated to detect bad actors disguised as humans, a mirrored version of the Turing test is used frequently. This very subject and its solutions was discussed by Alizadeh, et al., pointing to reCAPTCHA, Googles advanced AI detecting algorithm. Additionally, it was posited that a user centred design is needed for an additional ‘human touch’, as more reliable and sharper bot detecting algorithms are created (Alizadeh, et al., 2022). Returning to more solidified worries of AI creating an artificially made environment online, another respondent shared their concern on this question.

“Yes, I have a certain degree of concern. Although AI and related algorithms have brought a lot of convenience and innovation to social media, there are also some potential problems. For example, it may lead to an information cocoon, making the information people receive narrow and single; it may also be used to spread false information and mislead public opinion.”

Interestingly, an information cocoon, something that occurs when the individual is only being exposed to a certain type of information, is a direct amalgamation of a filter bubble. Additionally, information cocoons, a phrase coined by Cass Sunstein (Sunstein, 2006), have been proven to exist by academic literature, with a less controversial existence than filter bubbles despite the similarities. When coupled with economic theory, information cocoons can be viewed as a product of homogeneity rather than heterogeneity, with it being argued that despite the surface appearance of information cocoons removing the option of freewill from the decision making of the user, the cocoon itself is a product of their free behaviour (Yang, 2024). There is very little difference in information cocoons and filter bubbles, the real difference seems to lie within the scale that they encompass. Filter bubbles can deal with ecosystems of online users, whilst information cocoons often refer to the individual rather than a group or community. The term filter bubble is also preferred by academics in their research (Lun, 2017), as alternative terms like echo-chambers can be seen as more derogatory and has often been used by politicians and polarised opposing communities. Whilst there is a heavy focus on the idea of being insulated within a personalised experience, there is equally a focus on the spread of misinformation. Referring to the literature review and (Srba, et al., 2023) specifically, this is something that academics in the various fields of AI research are also primarily concerned about, hence the intuitive solutions such as misinformation bot detecting AI that is currently in the works. There was also a concern over the regulation of a rapidly advancing AI, something that has also been previously discussed in this dissertation.

One respondent answered.

“There is a complete lack of regulation and understanding about the effects of AI on the Environment, and that of Artists’ livelihoods.”

As previously discussed in the literature review, with the speed that AI is evolving it is pivotal yet incredibly hard to keep up to date with its iterations. Due to this, new tools must be designed to both monitor the rapid changes and regulate and even contain the abilities of AI online (Rodilosso, 2024). The respondent to this question further mentions artists’, this is something that has seen issues also as AI replicates the works of any artist that’s content it consumes. There are problems with the current form of AI and its ability for image creation, something that was discussed in greater detail during the interview. In the interview, the participant was asked ‘Could you tell me what you think artificial intelligence is?’. This question, although simple, was integral to the research as many people perceptions of what AI is differs substantially. The participant expressed a doubt in its artificiality and intelligence, stating.

‘It is scraping the web for content without any kind of intelligence. So, the fact that it’s scraping means that somebody, somewhere has programmed it to do that. So, it’s absolutely human made.’

There is truth to this answer, as AI is not truly sentient in the sense that humans are, and because of this it cannot truly act on its own accord without some human base or input. The interview moved on to issues around AI in creating art and replicating images, with the participant explaining why they perceive it to be fundamentally incapable of producing a true creation.

“All the famous things that AI does like present you with images of people with the wrong number of fingers and absurdities like that and just evidence of the fact that there is there is no thinking brain behind this. It is an amalgamation that’s clunky and clumsy in some ways.”

The participant went on to further discuss the over-dramatized impression that many have of AI, when prompted by a question surrounding the role that AI plays currently.

“Possibly the role it has online as far as I can see is somewhat overemphasised and makes people worried about what it might be up to in the background as though it was a force. So, I think it’s been humanised, anthropomorphised and put up as like the bogeyman.”

This opinion very much falls in line with the book ‘Why Machines Will Never Rule the World’ (Landgrebe & Smith, 2022). The book posits that humans are capable of a central nervous system and an organic biological brain, something that AI is unable to replicate. They evidence an array of hard science subjects such as Physics and Biology, along with Mathematics to evidence their point in the robot and biological divide (Landgrebe & Smith, 2022). Although there is a lot of merit to this stance, there are legitimate concerns surrounding AI involving the spread of misinformation and job shortages. The manufacturing industry could lose as much as 20 million jobs to automation and the integration of AI in low skilled work. Furthermore, up to 375 million jobs world-wide are estimated to be lost to automation by the year 2030. This amounts to around 14% of the world’s workforce, and even traditionally safer jobs such as those requiring a bachelor’s degree are at risk, as 24% of bachelor’s degree work has a risk of automation (Teamstage, 2024). Another interesting point raised by the participant was the source of the information used by AI.

“And you know, humans like me and other people have gone on to Wikipedia pages and put complete nonsense just for our own entertainment.”

This has seen AI face criticisms multiple times, as people share memes and articles surrounding AI giving terrible advice or offensive rhetoric due to manipulated data sources. One of which was when asked about increasing the stick of cheese to a pizza, Google AI suggested trying glue (Gillham, 2024). This is another potentially under studied aspect of awareness and AI, the potential for us manipulating the data sources rather than AI manipulating our data. The interview moved to another interesting point, and one that will end this section, how AI is creating a more conscientious digital footprint.

“Internet hygiene, as people used to call it. I don’t know if that’s the modern term, but I’m quite careful about when I have a possibility of refusing cookies or refusing data sharing. In particular on social media sites when I have the opportunity, like recently with Facebook to refuse that. For my data to be scraped by AI and then used to sort of feed the algorithms, I made sure to do that.”

With new laws in place where sites must inform users on how and why their data is being used, the idea of what an individual’s data is and how important it is having entered the public psyche. This is perhaps one of the more predictable yet profound behavioural changes of an awareness towards AI. We are aware that our data is being used, many of us do not know exactly what for, but we know that it is our personal data and there is a desire by giant tech firms to own it.

5: Defining The Filter Bubble

Question 6 of the survey was an integral question, that begun by providing a definition of the term ‘filter bubble’ so that ambiguity around meanings could be avoided. The question reads as follows ‘A ‘Filter Bubble‘ is a personalised online experience tailored on past interactions with content on the internet. Have you noticed a filter bubble within your own online experience?’. For this a linear 5-point Likert scale was deployed, with an answer of 1 meaning ‘Not at all’ and 5 being ‘Very much so’. Unsurprisingly, answers 5 and 4 received the highest number of responses, with 5 totalling 30.4% of the responses and 4 reaching 27.7% of the responses. This highlights a high level of awareness regarding personalised online experience being propagated by artificial intelligence. The middle ground answer (3) received 18.8% of answers, with the lowest response rates being answer 1 (13.4%) and 2 (9.8%). This question was marked by an asterisk, so it received all 112 responses available (See Appendix C).

For the open text box question that proceeded this, specific examples were requested. One respondent implied that they did not realise they were within a filter bubble until they compared their social media with their partners.

“Only when showing something to my partner and they see it show differently”

Another participant spoke of a less mentioned aspect of content personalisation, the geographical area we inhabit effecting our information flows.

“I can see that you can navigate lots of content and skew that to get more content on X. I then to watch videos on things I want to learn about to get more content on that. I also get location-based content which is a poorer way to target and personalise. Content has a material nature to it, so you need to be aware of this and deal with the socio-material qualities and actions that content and the system might engender in different groups, and demographics. I wonder if a lot of the content is accessible for a lot of users and how people from different groups deal with that.”

Interestingly, filter bubbles could act as a sort of propaganda machine when considering that information that is pushed may be specific to what area it is being pushed to. There is already an issue within academia and media in general to westernise or become western-centric/ euro-centric when it comes to methods of investigating and delivering information without bias. There is a further point that academia and social sciences have adopted over the years in decolonialising both thought and the methods we use to extrapolate information. However, if these views are being pushed heavily by AI algorithms, then instead of moving away from these practices, they may be strengthened, especially within public consensus. Issues surrounding this was discussed in a research paper by Makhortykh and Wijermars in relation to Easter Europe specifically. They discuss how the focus of filter bubbles has been its ability to affect the democracy of the region, pushing agendas to sway voters. When looking at Belarus, Ukraine and Russia, where freedom of press is different to western countries. The plurality of information that differs in the west makes it hard for a singular narrative to be pushed absolutely, hence the creation of high polarisation levels in democratic countries. Additionally, there is a large linguistic discrepancy, something that makes easter European academia have a hard time engaging with western and English-speaking European academia (Makhortykh & Wijermars, 2023). Potential propaganda or the pushing of mainstream agendas was something mentioned by another participant.

“Most recently I noticed that Facebook started pushing various maps, history and architecture pages onto me. These are subjects I like, so probably I have pressed a link somewhere a long time ago – but the posts it promotes now are of no interest to me. Likewise with YouTube, I noticed how bad it has gotten over the past few years with inserting pro-Ukraine propaganda into any related videos sections, vaguely related to what I watched before but clearly promoted on purpose. I had to resort to turning off all suggested videos to put myself back in control over the content that I watch.”

With another respondent even having their perception of a vote-based outcome skewed due to their personal filter bubble.

“IN the Brexit referendum it appeared remain would clearly win to me because of the feed content I received. Clearly this was not the case.”

The potential methods of data gathering that are also lesser discussed, such as our devices listening into our private conversations for key words to recommend us further content or items was also mentioned by one participant.

“Having adverts or video suggestions based upon recent topics of discussion or viewing almost feels like an invasion of privacy as you are subjected to what they think you want rather than freely discovering new avenues.”

This form of personalisation creation is known as voice data, something that many phones and other devices do without most people realising. There are a host of issues with this, the violation of privacy or perceived privacy when discussing subjects, the unwanted personalisation that can accidentally be discriminatory due to misunderstandings of the voice data. To many advertisers who have ties with Google this is seen as an untapped wealth of information that can drastically elevate their business and marketing models (Turow, 2021). The source of most audio data that is recorded for recommendations and personalisation comes from personal assistants ran by the phone’s maker, often Google Assistant for androids and Siri for Apple devices. In a survey conducted on people who have noticed this version of a filter bubble, 70% of respondents confirmed that they had (Kenny & Trejos, 2024). The consent to do this often lies within the terms and conditions before the use of the new device has even begun, or through updates to the device’s software and applications. One of the key research points of this dissertation was to find out how people change their behaviour when confronted with a filter bubble narrowing their information flow online. This was something discussed in the answer below.

“My partner and I have hugely different YouTube channels, because of our watch history. When my partner wiped and restarted their channel, the content went down a different “pathway” and there are whole channels that never got recommended. I worry about being in an echo chamber. I don’t like or use Facebook and I hate the way it recommends people based on algorithms to make me keep perpetuating the cycle.”

For many, resetting the entirety of their personalised data can seem undesirable, as though there may be things within the content that are unwanted, much of it is personalised to your specific interests. As this respondent wrote, the clean slate allowed for a new filter bubble to be created, and this led to a discovery of new novel content that had not previously been seen. Perhaps a clean out of personalised data is something that should be implemented on a monthly basis, so that whilst filter bubbles are created, they are equally popped before the walls become too thick to escape for many.

Question 8 was an open text box, asking ‘Do you feel the creation of a filter bubble in personal social media use can be limiting? Please explain your answer briefly below.’. A strong answer given by multiple responder’s was that filter bubbles are unable to factor in the changes and transformations that a human goes through. Filter Bubbles build a content ecosystem that polarises against other ecosystems from other communities online. The conflicting nature of humans and their ever-changing thoughts and feelings is something that is still alien to AI and separates machines from people. Below are examples of participants answers to this question that mention these issues.

“Yes, as it does not take in the ability to change. Most people change weekly if not daily their tastes, opinions, like etc.”

“Yes, as your past interactions may not align with who you are now.”

“Yes, it stops me from learning new things on sm.”

“Yes, because of confirmation bias and a dampening of curiosity.”

“Limiting to the creator because it falsely assumes that behavioural patterns and choices will always be similar which is a false assumption.”

Another participant spoke of the insular nature of filter bubbles, but also mentioned the lengths that social platforms are going to prevent this.

“On the one hand, with the continuous improvement of people’s understanding of the diversity and objectivity of information, many users began to consciously and actively break through their information comfort zone and actively pay attention to and search for different views and types of content, which can break the shackles of filtering bubbles to some extent. On the other hand, social media platforms are gradually aware of the problems caused by filtering bubbles, and take some measures to improve them, such as adjusting the algorithm recommendation mechanism and increasing the content of random recommendation or popular recommendation to show more diversified information.”

6: Likelihood of Change

As previously discussed in both the literature review and the discussion around bots plaguing online spaces, there are algorithms such as Google’s reCAPTCHA that are working to prevent false online spaces. The issue with creating hypothetical pins to pop our filter bubbles is that advertisers use these algorithms to generate money from us. Statista currently pins the amount of money spent on online advertising efforts at $667 billion dollars as of 2024, with this amount estimated to elevate to $870 billion by 2027. As of 2021 (where the total sat at $504 billion) that is an estimated growth of $364 billion dollars in six years (Statista, 2024). With the levels of money being made and spent and the algorithms designed to push these advertisements on us, it is hard to believe that online elites will choose ethics over capital. Additionally, the two richest people on Earth, Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, both own the largest online spaces on the internet (X and Amazon) (Moskowitz, 2024). With the potential of another AI winter looking unlikely, AI is set on a course of rapid growth and expansion into daily lives. One of its key features is pattern recognition, and there is no better way to consume large quantities of data on human patterns than our social platforms. Due to this, AI in this authors opinion, is more likely to be further utilised to commodify our behaviour than try and change it so that we become more complete in our views and beliefs. The surveys have shown that many people are noticing the effects of filter bubbles in their online spaces, and some are considering changing their behaviour to escape these bubbles. As the next question shows, whilst many people agreed that they were changing or going to change their behaviour to rectify the issue of insular content, still, 41.1% felt that they were not going to.

Question 9 asked ‘Has an awareness of the role of AI and algorithms changed your behaviour online, or will it change your behaviour online? e.g. exploring content outside of your filter bubble, avoiding personalised ads’. This question looked to explore the potential of awareness in the form of the definition of the filter bubble, and if previously unaware of this, the change that it could elicit. The answers comprised of 5 options, with 1 being ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 being ‘Strongly Agree’. The highest percentiles were on the side of changing behaviour to avoid a filter bubble, with 5 receiving 17.9% and 4 being the most popular option at 44.6%. The lowest answer respondents selected was 1 at just 4.5%, meaning that most responses are in favour of escaping a filter bubble (see Appendix D).

This again was marked by an asterisk, and it received all 112 responses. Interestingly, the jump from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘agree’ had a difference of 26.7% or over a quarter of respondents. Answers 3 (Neutral), 2 (Disagree) and 1 (Strongly Disagree) collectively shared 41.1% of the 112 responses. One respondent discussed the importance of addressing every side of information and its context, so that the most informed opinion can be garnered.

“I stop AI from harvesting my data where possible, when I am aware that I have a choice, e.g. on Facebook posts. When I have an important decision to make, like in elections, how to vote, or in response to proposed laws or amendments to laws, or policies, I will ensure that I investigate multiple sources. This might include left, right and green political parties, groups that comment on national policy and corporate as well as watch dog organisations.”

Whilst many people are aware of AI and its personalisation aspects, an interesting follow up study would be to investigate how aware people are of the methods in which it collects their data. With Threads and Instagram, both owned by Meta, collecting 86% of its user’s personal information (Radauskas, 2023). One participant felt strongly that they were having information not just filtered, but hidden from them by Google, as it did not fit a profitable or ‘mainstream’ narrative.

“I’ve almost stopped using Google because of its filtering of the results that may be considered not compliant with or opposing the USA regime ideology propaganda. It started quite innocently a few years ago – for instance, you couldn’t find information on certain international events if they involved USA adversaries, but lately it became so bad with the whole wokeism and globalist agenda that you can never find a news article or an independent opinion, or even goods and photographs on topics that is of interest to you. It’s fine as long as your search query isn’t related to race, medicine, gender, history, politics or religion. But for everything else I have to use other search engines. Also, as I mentioned before I had to start using browser extensions to revert or limit the news feeds to avoid seeing the “related” content that the company wants me to see.”

When investigating this further, it is found that Google and its AI chatbot had recently been programmed to not show or answer certain questions involving the assassination attempt of Donald Trump. Google directors claimed that this was to stop political violence spread and misinformation. Additionally, claims that Google’s predictive search AI was politically bias had been disproven, as users who typed in ‘President Ba’ had suggestions for ‘President Barbie’ rather than ‘President Barrack Obama’ (Cercone & Swann, 2024). When studies have looked further into this regarding social platforms, they have found that certain ones are less reliable than others. Facebook was the largest offender for AI misinformation, whilst TikTok produced a high amount of misinformation, a lot of it was deemed as satire. Within US Google searches, it has been found that Liberal sources outnumber Conservative ones at a rate of 6:1 (Rogers, 2021). If this is down to a political bias or because Libertarians are more vocal online is still down to opinion. However, this raises an interesting conundrum, can we fall into being hyper-aware of the information being presented to us. Whilst extreme vigilance on the information being presented to us is not an inherently bad thing, it can lead to a potential overreaching distrust and an absolute rejection. The aspects of hyper-awareness of AI is another area that could benefit from more research as this area is lacking within academia. Critically assessing the information being presented to you is always a good thing, even if it reinforces your beliefs.